In Ghaziabad, a bustling part of the Delhi National Capital Region, doctors at a government hospital despairingly watch a newborn fight to breathe. The infant needs specialized treatment that the facility cannot provide, but its chances of surviving the journey to another hospital are dim. As a last resort, the doctors strap the baby to the father’s chest, breathing tube and all, and in that womb-like position, send them to a critical care facility about 30 minutes away. Against all medical odds, the infant survives the journey, a testament to the healing and restorative power of the human touch.

The Ghaziabad baby is not alone: The world over, thousands of babies are adjusting to life outside the womb not in incubators in hospital nurseries, but on the warm chests of their parents (or other caregivers). This is kangaroo mother care, modern medicine’s latest protocol for babies born prematurely or underweight — and a long-standing traditional midwifery practice. It derives its fetching name from female kangaroos who keep their infants warm and stable in a pouch on their bodies, and essentially entails keeping the infant skin-to-skin with the mother or caregiver after birth as well as breastfeeding. This immediate skin contact provides warmth and protection from infections while also aiding stress relief and emotional bonding.

Globally, one in every 10 babies is born prematurely, arriving before completing 37 full weeks of gestation, which elevates the risk of severe and persistent illnesses, disabilities and developmental delays and even threatens their survival. An estimated one in five babies exhibit low birth weight (less than 2,500 grams or 5.5 pounds). With minimal body fat, such infants are often not able to breathe on their own, gain weight or regulate their own body temperature.

“As soon as they’re born, such babies need to be protected from infections, exclusively breastfed, given gentle breathing support and kept warm, to improve their odds of survival,” says Delhi-based Harish Chellani, neonatologist and researcher. Traditionally, midwives would place the newborn on the mother’s chest immediately after birth to achieve this, but 20th-century medicine placed its faith on a machine that simulates the womb: the incubator. Incubators gained currency in the early 20th century, believe it or not, as displays at the Coney Island amusement park in New York City. Visitors could peer through a glass front to see doctors and nurses caring for premature infants in peculiar metal incubators that simulated the womb. The exhibit’s popularity helped incubators go mainstream and eventually become accepted as essential medical care for premature babies.

In 2017, Chellani, along with medical researchers in five tertiary care hospitals in Ghana, India, Malawi, Nigeria and Tanzania, began studying whether kangaroo mother care (KMC) could be used for every preterm baby, whether stable (broadly speaking, those able to breathe, feed and regulate their body temperature on their own) or not. They randomly assigned unstable newborns with a birth weight between 1 and 1.799 kilograms to two groups. Group 1 received immediate KMC, where the mother or caregiver provided up to 17 hours of skin-to-skin contact per day in a mother-newborn ICU. Group 2 received conventional care in an incubator or warmer until the baby’s condition stabilized, followed by KMC.

“We had to halt the trial prematurely in January 2020,” Chellani recalls, as they observed a 25 percent reduction in preterm deaths, 35 percent reduction in incidence of hypothermia and 18 percent fewer infections in the immediate KMC group, compared to babies in the control group. “We collectively decided we couldn’t deny what had clearly proved to be a life-saving protocol, to the control group babies.” Globally, the researchers estimated, immediate KMC could save 150,000 lives every year.

The practice of kangaroo mother care in modern medicine was developed by physician researchers Edgar Rey Sanabria and Héctor Martínez-Gómez in 1979, in Bogotá, Colombia, as a solution to the shortage of incubators. Subsequent research showed that this simple and cost-effective stratagem was as successful in treating clinically stable but low birth weight infants as the NICU. By 2003, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended it for low birth weight and preterm babies with no major health problems and able to breathe independently. Research in the next 10 years showed that KMC helped reduce infant mortality, regulate body temperatures and even, as Chellani points out, seemed to decrease stress levels.

The trial that Chellani participated in showed that unstable newborns also had a better chance at surviving and thriving with KMC. After the study was published, the WHO issued new guidelines in November 2022 advising that all babies have immediate skin-to-skin contact with a caregiver after birth — without any initial time in an incubator, irrespective of the baby’s birth weight, gestational age or stability.

In many ways, KMC is, as the WHO’s Shuchita Gupta puts it, “a return to the basics.” Gupta, medical officer (newborn health) in the organization’s department of maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health and aging, describes the ideal KMC protocol: Newborns are securely wrapped on the caregiver’s chest immediately after birth, and naturally home onto the breast to feed.

This contact soothes and nourishes, helping even babies with low birth weight and breathing difficulties to recoup. And even though it is called kangaroo mother care, newborns respond to skin-on-skin contact with other caregivers — dads, grandparents and even trained volunteers. This not only gives mothers much-needed respite but also offers other family members (including adoptive and surrogate parents) the chance to bond with the newborn.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

“It is an absolutely beautiful sight,” says Aarti Kumar, who, with her husband, Vishvajeet Kumar, heads Community Empowerment Lab (CEL), a public health research organization in the northeastern state of Uttar Pradesh that has helped the state government to develop over 315 KMC “lounges” in government facilities. The CEL recommends a minimum of three days of KMC for all babies, and for as long as it takes for sicker babies to get better.

About 250 miles east of Delhi, the Kumar duo analyzes data on infant deaths in their lab. Uttar Pradesh has one of the highest infant mortality rates in India. “One-third of these deaths can be attributed to infection, another third to low birth weight and the remaining to breathing issues,” Kumar says. “And up to 80 percent, we reckon, can possibly be prevented by properly implemented KMC.”

The question is, how does KMC benefit the infant? In many ways, research shows.

The caregiver’s skin and heartbeat sooth and warm the infant. Chellani has observed that this reduces stress, measured through the levels of cortisol in the saliva. The contact is also crucial for developing a healthy skin biome (human skin is home to diverse beneficial microbes, which are the newborn’s first line of defense against infections) — something that preemies often lack because of early or prolonged antibiotic use and hospital stays. Skin-to-skin contact facilitates the transfer of these microbes to the infant, which reduces infection rates. The prolonged contact with her baby improves the mother’s breast milk production. All in all, with better warmth, lowered infection rates and improved feeding, KMC helps infants sleep better, and even accelerates brain maturation.

In spite of robust proof of its efficacy, and the fact that KMC was recommended by the WHO as the evidence-based care regime of choice for preemies back in 2022, it has not yet become mainstream. The world over, incubators remain the cornerstones of newborn care, and Kumar says that they have to “prove to hospitals again and again that KMC is as ‘safe’ as an incubator.” Also, existing NICUs are sterile areas that mothers and caregivers are able to access for only short periods of time. Convincing doctors to allow mothers and other caregivers in NICUs, at the risk of potential contamination, has been hard.

Gupta points out that in order to scale KMC across the world, maternity and neonatal wards in hospitals need to train doctors and nurses, follow a scientifically researched, evidence-based protocol, and revamp medical infrastructure. “One would think the mother just needs to keep the baby on her chest and that’s it…” she says. “But it’s not as simple as that.”

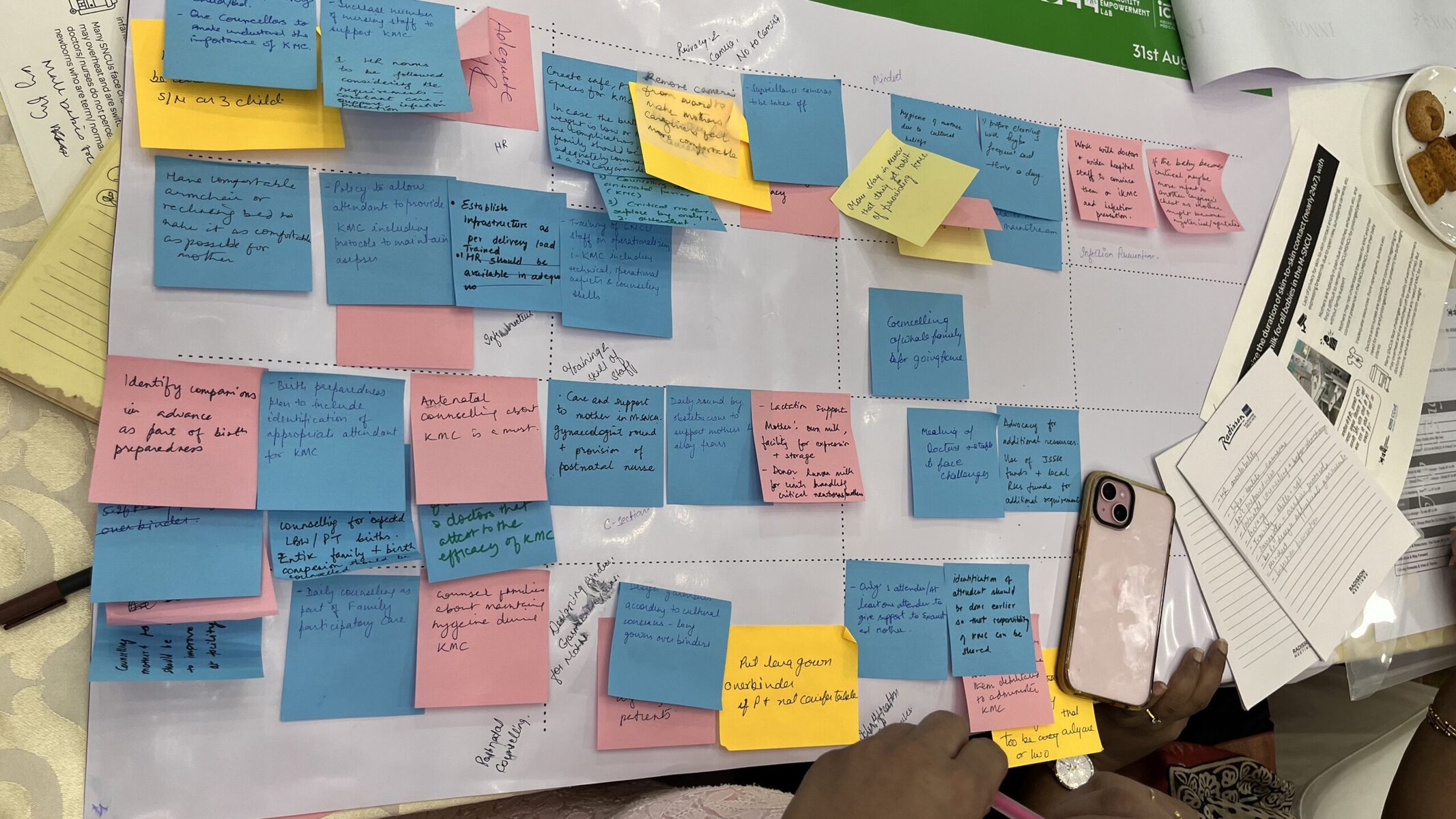

In August 2024, the Community Empowerment Lab brought together over 50 neonatologists, OB-GYNs, pediatricians, nurses and public health officials to brainstorm NICU designs that would enable KMC. Most participants agreed that existing medical infrastructure would need substantial upgrades to support the protocol, citing the lack of privacy in the wards, understaffing and an acute shortage of space as barriers.

A NICU nurse remarked that it was “as good for the mother as it was for babies,” but other participants felt the protocol could place undue burden on mothers still recovering from childbirth unless their families were on board. Heartbreakingly, one participant observed that some families were willing to provide KMC to infant boys, but not to girls. Gupta, also one of the workshop participants, said unless more and more doctors are able to experience how lifesaving KMC can be, they may not buy in easily to a protocol that relies less on technology and more on touch.

Kumar listened to the lively debate. An engineer by training and public health advocate by passion, she is helping design one of India’s first KMC-enabled special newborn care units at the Ghaziabad district hospital. “We need such facilities, sooner the better,” she says. “For we now know that more than science and modern medicine, the most powerful treatment for a premature, underweight infant is their mother, no matter if she is educated or illiterate, rich or poor … I think that’s amazing.”

The post An Age-Old Midwife Tradition’s Revival Is Saving Vulnerable Newborns appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.