As the White House changes hands, America seems more polarized than ever. Though it may be tempting to retreat into our silos, bridge builder and journalist Mónica Guzmán would caution us not to.

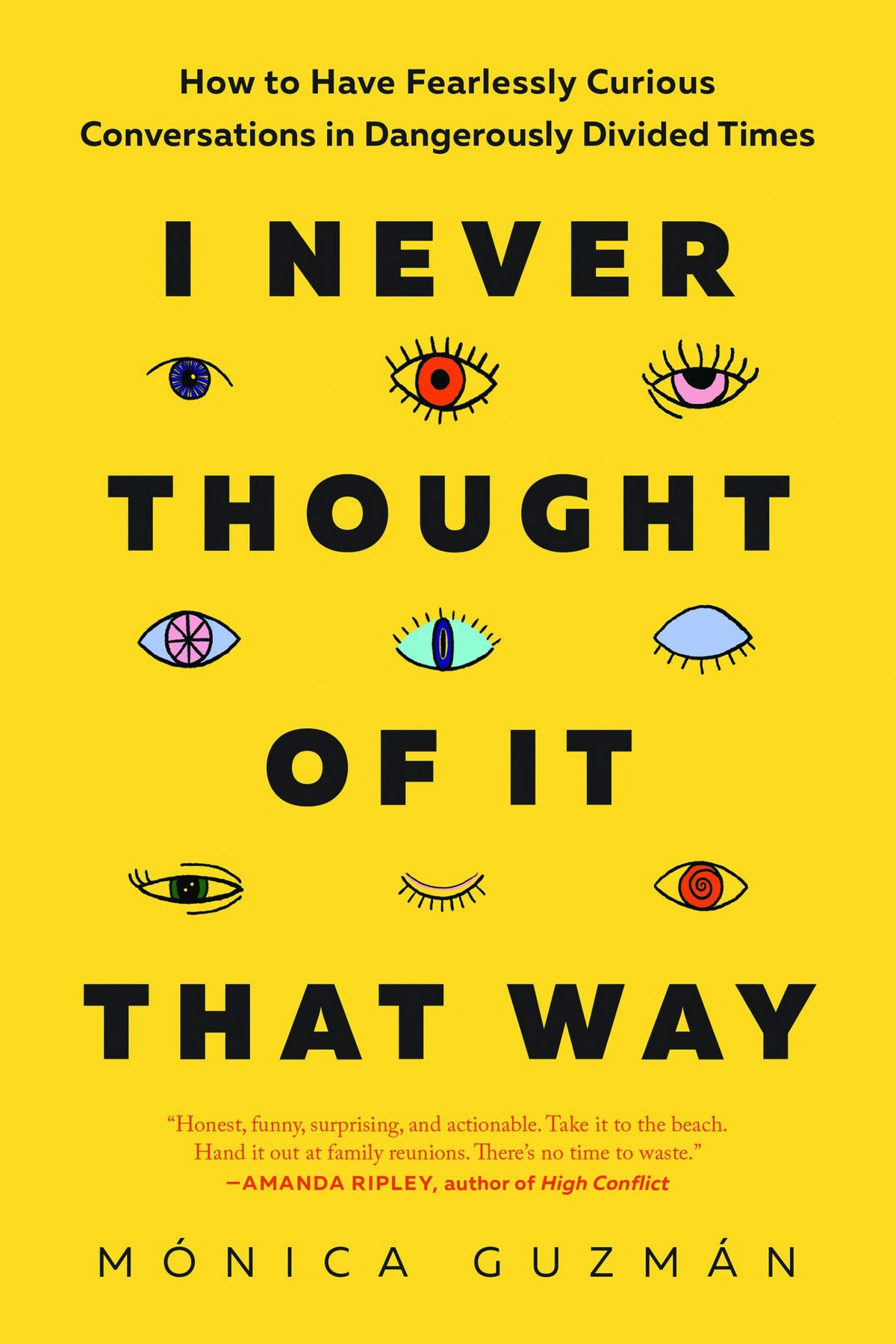

In her book I Never Thought of It That Way: How to Have Fearlessly Curious Conversations in Dangerously Divided Times, Guzmán shows us why siloing — particularly in our digital worlds — can lead to dehumanizing the “other side.” In the book, she explains the importance of remaining curious and building bridges. She also reveals the magic of an “I never thought of it that way” (INTOIT) moment — when something surprises you, challenges you or freshens your thinking — and why we should seek out more of these moments.

A liberal whose Mexican immigrant parents have voted for Trump three times now, Guzmán has personal experience talking to the “other side” with respect and curiosity. Though she does not agree with her parents on most political matters, she understands them. Guzmán is also senior fellow for public practice at Braver Angels, a cross-partisan organization dedicated to political depolarization, and hosts a podcast, A Braver Way.

Recently out in paperback, I Never Thought of It That Way offers a step-by-step toolkit to ditching your assumptions, getting outside of your silo, embracing complexity and staying insistently and ferociously curious. RTBC spoke to Guzmán about where to read less-biased journalism, why misinformation flourishes in a culture where we can’t talk to one another, and how engaging with people who think differently than we do helps build lasting social movements.

You write that you had an INTOIT moment while reading an article in the New York Times about protests against the COVID shutdowns. The story complicated your assumptions about these protesters and got you to see where they were coming from. Even though “the media” is vilified by both left and right, do you think that journalists have an important role to play in listening to — and reporting on — the “other side”?

They do. And you’re hearing sadness in my voice because I don’t believe that that part of the job has been fulfilled to its potential. I think journalists could play an extraordinary role in helping people see that about each other. What if more of our stories included not just what you know — why Mary Sue hates this policy — but tell me one thing about Mary Sue’s life that helps me understand why that resistance to that policy is coming out of something she loves or supports. Or something she’s afraid she’ll lose. That is so much more true than giving me a logical book report-type answer that doesn’t help me see people. I no longer think that reporting on issues without reporting on the people whose concerns animate the debate is useful.

To those of us who identify more with the Left, it sometimes appears as if lots of the reaching out is happening in one direction, with blues trying to understand reds.

Can you think of examples of right-wing media trying to understand Democrats?

The election put one side on its heels, not the other, so it makes perfect sense that there’s more reckoning and curiosity on the losing side than the winning one.

In the book I talked about certainty and fear being arch-villains of curiosity. Since I published the book, I’ve spent a lot more time being drawn to the internal work of curiosity. And out of that has come an interest in the trauma response.

Fear is so important to understand. The theory I’m playing with is that in 2020, we were super polarized, of course, and when the right lost — you know how there’s “fight or flight” trauma responses? What the right did was fight. So there were many folks who said, “No, we didn’t lose the election.” There was a fight against the whole narrative that they had lost. They fought and they fought. And then in 2024 the blue side lost. And if I were to look at the trauma responses, I would say the response of choice was flight, not fight. The blues didn’t fight the result of the election, but they fled from people in their lives who would have supported that.

You write in the book’s introduction, “I’m done, too, going along with the idea that if we could just rid the world of ‘misinformation’ everything would be fine. As if mowing down weeds would keep new ones from sprouting. … Misinformation isn’t the product of a culture that doesn’t value truth. It’s the product of a culture in which we’ve grown too afraid to turn to each other and hear it.” Can you say more about this?

I wrote that line in 2020 and I believe it so much more now.

As a journalist, I’m steeped in a certain way of thinking about truth — it’s really just about facts. It’s about what happened, what didn’t happen. And it’s easy to include in what happened and what didn’t happen, not just, “The Syrian leader fled Damascus to Moscow,” but also why. Why the Syrian leader fled to Moscow, and whether it’s good or bad, and what America’s interests are now. And those questions are about interpretation of events, and those are not necessarily in the same category as factual things. But I think that they can get really easily conflated as being all one package.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.

That’s problem number one. People start to think that if someone has a different interpretation of events, that they are denying facts. And then we start to draw lines between each other and say those people are unqualified to have this conversation because they don’t see my facts. But what they’re really disagreeing with you on is the interpretation.

What I really meant in that line was that what people are concerned about is a form of truth. It’s a deeply relevant form of truth that we don’t value.

Later in the book, you mention a project called “Walk a Mile in My News,” founded in 2021 by Wynette Sills, who was part of the Braver Angels group in Sacramento. The idea is to get out of your media silos by a) reading articles from the other side of the political divide, and b) getting to know someone who appreciates what those articles are saying.

This seems a radical concept. Would you say it’s successful? Do you see any other good signs of the depolarization of our media?

I do think it’s successful. It’s been picked up by a lot of Braver Angels chapters across the country. I wrote a blog post about this program a few years ago.

I’m really excited about the news outlets that are getting more popular because they are making a practice of making their work resilient against overly polarizing habits. My favorite example is a guy named Isaac Saul. He created a newsletter called Tangle News. He was invited to do a main stage TED Talk in the last year. His newsletter has been growing like gangbusters. For years, he’s been at war against partisan-leaning news that doesn’t serve the public and doesn’t serve our collective search for truth. There are a lot of folks at Braver Angels, and a lot of folks in the bridging space, who read Tangle News.

My other favorite one is called The Flip Side, which was started by my friend Annafi Wahed. The Flip Side picks one political issue a day, gives you the best commentary from the right and the best commentary from the left — just like a paragraph. And every time I read The Flip Side — whatever judgment I came in with — I usually still agree with my side of things, but I leave a little more room for, “But I want to know more about that thing that the other side is saying.” Or, “Why didn’t my side report on this detail?”

Are there other daily ways of eavesdropping on the “other side’s” media?

My mother sends me articles that move her. Reading them, I’ll follow my own advice. I tell folks to practice curiosity across the divide in this “safe” way where they’re not actually in conversation with someone, but instead are just reading an article by the other side. And the two pieces of advice I give are first, as you read the article, ask yourself, “What’s the strongest argument on this other side?”

And then I also ask myself, “What are the deep-down honest concerns that are animating this perspective?” And that’s super important. It can be very hard to do, because sometimes what you’ll hear is so much anger and hyperbole. And so the trick is to try to get behind the anger and hyperbole. To ask yourself, “What’s motivating this? What do they think is really under threat?” Those questions can be so cool.

What recommendations do you have for people who are stuck in their silos and don’t know many people who have different political beliefs than them?

There is an organization you should know about: The American Exchange Project. It’s basically an exchange program to connect people across the urban-rural divide. It helps high school seniors travel and meet youth from different sociopolitical backgrounds. It’s awesome!

For Braver Angels, we have 100 chapters all over the country. If you don’t have a chapter near you, you can start one. And some chapters are just so active and so amazing — there’s always something going on. It’s just regular people.

What do you say to individuals who hesitate to be involved in bridge-building interactions because it feels like selling out their values, or due to concerns about personal safety if those they’d be interacting with might hold more discriminatory views on social identities to which they belong?

There’s so much to say on this.

One is that it is impossible to have a curious conversation when you are afraid. So no, if there is a sense of the lack of safety, if there is a deep fear, if your brain is only capable of those things, it’s not going to work anyway. So forget it. Take yourself off the hook.

As an example, when it comes to trans issues, the stories and the rhetoric out there are not exactly encouraging a sense that you will be received with compassion. Which, to me, is a problem with our media. It is not representative of people’s hearts. And I’m pissed off about that!

But all that said, no wonder people are terrified. And there are real policies being put forth. On the Braver Way, I interviewed Kai Cheng Thom, who’s a trans woman and an advocate and an extraordinary bridge builder. The kinds of things that for me are a headline are for her extraordinarily impactful, right?

But here’s where I see things differently. Everything I have learned about social movements that endure, actually persuade people, bring people along — that sustainable kind of movement tells me that flight doesn’t work. If too many people take the flight path, then we’re just going to keep bouncing around like ping-pong balls, not having the debates we need to have, and not advancing more common-sense policies that are compassionate and nuanced.

Go slow. And for crying out loud, don’t engage with someone on social media! Get one-on-one with somebody you trust on everything, but you have this one thing. Find the place where you are safe enough to be curious — your edge. And if you listen to Episode 17 of a Braver Way with Kai Cheng Thom — talk about courage. Here’s this trans woman who absolutely has seen her way to engaging with the other side. She is a fierce activist. It’s not one or the other. It really should be both.

The post How to Reach Across a Divide With Curiosity Instead of Hate appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.